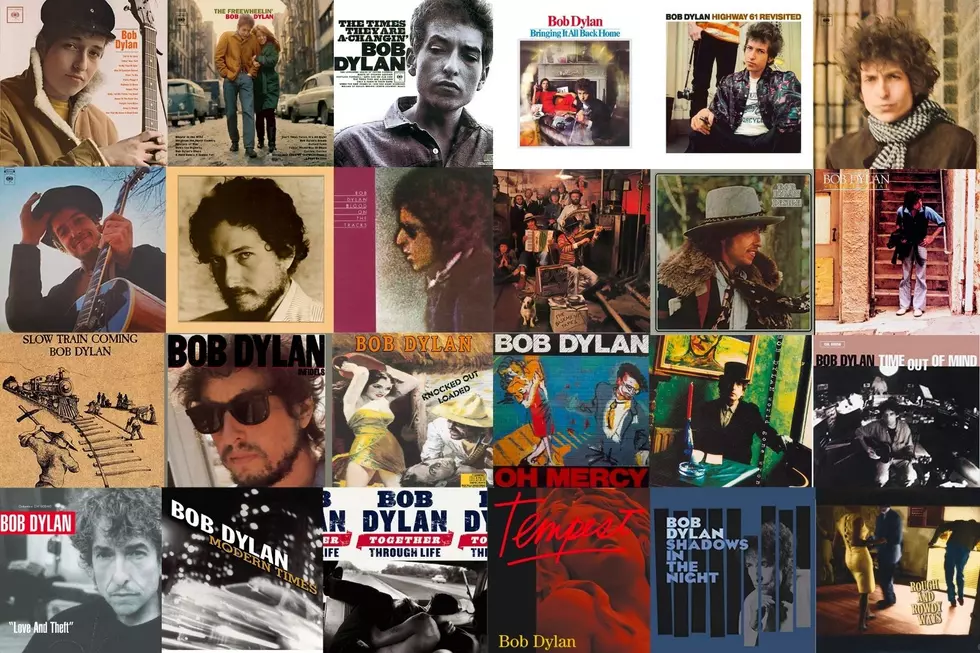

The Best Song From Every Bob Dylan Album

Bob Dylan was once asked by a reporter if he considered himself more of a singer or a poet. "Oh, I think of myself more as a song and dance man, ya know," he cheekily replied.

Like many of Dylan's responses to the press through the decades, it was cleverly charismatic and purposefully ambiguous. But it's perhaps the most straightforward answer he's ever offered in an explanation of his work. Since the early '60s, he's upheld his reputation as a song and dance man, albeit a tangled one. There have been plenty of moments throughout his career in which fans, believing they finally understood the method to the madness, were surprised when Dylan flipped the switch again: acoustic to electric, rock to religion, blues to ballads sung by Frank Sinatra.

For Dylan, there has always been an emphasis on constant movement. There is always something new to try, always a new way to reinterpret an old theme, always a way to think again. “Life isn’t about finding yourself or finding anything; life is about creating yourself," he said in Martin Scorsese's 2019 film Rolling Thunder Revue. Dylan has recreated himself time and time again throughout his albums. Below we try to get a grip on the legendary singer-songwriter by highlighting the best song from each of his studio LPs.

"Song to Woody"

From: Bob Dylan (1962)

Dylan penned only two original songs for his debut album: "Song to Woody" and "Talkin' New York." The 11 covers are important to his development, but it's the originals, and "Song to Woody" in particular, that display Dylan on the cusp of his writing talent. If anyone was qualified to write an homage to Guthrie, it was Dylan, who'd spent weeks visiting the ailing folk legend in the hospital as he suffered from Huntington's disease. Dylan was 20 when he recorded "Song to Woody," a tender tribute to one of his greatest influences, that, in true folk-singer fashion, borrowed its melody from Guthrie's "1913 Massacre." It proved cathartic. "I felt like I had to write that song," Dylan said in Scorsese's 2005 movie No Direction Home: Bob Dylan. "I did not consider myself a songwriter at all. But I needed to write that and I needed to sing it. So that's why I needed to write it. 'Cause it hadn't been written and that's what I needed to say, I needed to say that."

"A Hard Rain's A-Gonna Fall"

From: The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan (1963)

Dylan did not so much arrive in the New York City songwriting scene as burst into it. By the time of his second album, he had more than enough original material. Even though The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan contains such socially enlightened songs as "Masters of War," "Talkin' World War III Blues" and "Blowin' in the Wind," there's a more hypnotizing sense of hopelessness to "A Hard Rain's A-Gonna Fall." When the song was released, some thought it was a response to the Cuban Missile Crisis; others thought the "hard rain" was a direct reference to nuclear fallout. But the song wasn't inspired by just one thing. The 22-year-old Dylan was coming to grips with the harsh realities of the world. "After a while, you become aware of nothing but a culture of feeling, of black days, of schism, evil for evil, the common destiny of the human being getting thrown off course," he wrote in Chronicles: Volume One. "It’s all one long funeral song."

"Boots of Spanish Leather"

From: The Times They Are a-Changin' (1964)

"Boots of Spanish Leather" is a play in and of itself, in which there are only two characters and the ending can only be described as bittersweet. In less than five minutes, Dylan, plucking an acoustic guitar, illustrates a delicate yet deeply emotional conversation between two lovers, one of whom is bound for somewhere far away. The left-behind partner languishes a bit in despair, made aware that his "one true love" won't return: "I’m sure your heart is not with me, but with the country to where you’re goin’." He decides that a pair of Spanish leather boots will fill the void. The Times They Are a-Changin' is often lauded for its title track or politically moving topical songs like "The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll" or "Ballad of Hollis Brown," but in the midst of it all, Dylan bares his soul in "Boots of Spanish Leather."

"My Back Pages"

From: Another Side of Bob Dylan (1964)

Even in 1964, Dylan was able to look back at his first few years as a recording artist and recognize that the person he'd come to be known as — the protest-song-writing voice of a generation — wasn't who he was in private. Dylan in 1964 was cognizant of his disillusionment with the social-justice movement of the '60s, even going so far as to question how one can ever really tell the difference between right and wrong. He answers his questions by concluding that viewing life through such a serious lens is neither effective nor meaningful: "I was so much older then, I'm younger than that now."

"Subterranean Homesick Blues"

From: Bringing It All Back Home (1965)

It was only a matter of time before Dylan took a turn toward something different. Whether or not fans would follow him into electric rock music made little difference. Something had been bubbling just below the surface, and it boiled over at the top of 1965's Bringing It All Back Home in "Subterranean Homesick Blues." Musically derived from Chuck Berry's "Too Much Monkey Business" but lyrically closer in line with something out of a Jack Kerouac novel, the song features Dylan spitting out words using only one note at a pace, unlike anything he'd recorded before. In one of his most quoted lines, he emphasizes that there's no one voice, least of all his, who can tell you what direction to go: "You don't need a weatherman to know which way the wind blows." It's a whirlwind of a ride - from Johnny mixing up medicine in the basement to the missing pump handles stolen by vandals. Nothing would ever be the same again.

"Ballad of a Thin Man"

From: Highway 61 Revisited (1965)

"Ballad of a Thin Man," the final track on Side One of Highway 61 Revisited, is delivered like a knife to the rib cage. In a scathing, sneering tone, Dylan describes the aloof Mr. Jones, who finds himself in increasingly bizarre situations. The more questions he asks, the less sense it all makes. It's a horrifying funhouse of sword swallowers, camels and lumberjacks that Mr. Jones gets lost in, unable to find his way out. Dylan once noted that Mr. Jones was a real person. "You know him, but not by that name," he said in an interview with filmmaker Nora Ephron and editor Susan Edmiston. "Ballad of a Thin Man" still haunts listeners — something is happening, we just don't exactly know what it is.

"Sad-Eyed Lady of the Lowlands"

From: Blonde on Blonde (1966)

Not many artists in Dylan's sphere were including 11-minute closing tracks on their albums in 1966, but it's impossible to imagine Blonde on Blonde without "Sad-Eyed Lady of the Lowlands." The first stanza alone is enough to impress most skeptics, with its description of the sad-eyed lady who has "eyes like smoke," a "voice like chimes, "flesh like silk" and a "face like glass." Dylan wrote the song in a marathon writing session that stretched into the early hours of the morning, giving the song a placid nocturnal quality. It's the sound of the middle of the night as the tape recorder rolls.

"The Wicked Messenger"

From: John Wesley Harding (1967)

By 1967, fans were clamoring for Dylan to return to his acoustic guitar. He finally did so with John Wesley Harding, an album that mirrored his folk roots but also featured country and blues influences. The centerpiece for many listeners has long been "All Along the Watchtower," but there are other moments in which Dylan's curious, roaming mind manifests itself in song. Years before he transitioned to non-secular songwriting in the late '70s, Dylan took interest in the Bible, its characters and its stories. "The Wicked Messenger" appears to take its title from Proverbs 13:17: "A wicked messenger falleth into mischief: but a faithful ambassador is health." It may not be the album's most memorable song, but it's perhaps the best representation of its comfortable, meandering trot.

"I Threw It All Away"

From: Nashville Skyline (1969)

"I Threw It All Away" is one of the first examples of Dylan accepting responsibility and regretting his failures and shortcomings in relationships: "I was cruel, I treated her like a fool, I threw it all away." It's one of only two songs Dylan had written before recording sessions for Nashville Skyline began (the other was "Lay Lady Lay"). What or who Dylan had in mind when he penned "I Threw It All Away" can only be speculated, but it's another example of Dylan opening up and writing without too much rhetoric.

"Days of 49"

From: Self Portrait (1970)

Many Dylan fans and critics have a complicated relationship with Self Portrait, the intentionally chaotic 1970 LP Dylan hoped might help remove increasingly impossible expectations that were placed upon him. It can be a challenging listen, especially given its length. "I mean, if you’re gonna put a lot of crap on it, you might as well load it up!" Dylan told Rolling Stone in 1984. Still, some spots of intrigue and downright fun can be heard, like in "Days of 49," based on a folk poem by Joaquin Miller first recorded by Jules Verne Allen, the "Original Singing Cowboy," in 1928. Additional verses were added over the years. Dylan's rendition lopes from verse to verse, telling the story of a gold miner during the California gold rush of 1849.

"Sign on the Window"

From: New Morning (1970)

On the heels of Self Portrait came New Morning, a more serious album where Dylan laid out his desires to live something approaching a normal life. "Sign on the Window" showcases his distinctive style of piano playing as he considers what it may have been like to live in a cabin in Utah with kids who call him "Pa" and where he fishes for rainbow trout. It's an extreme idea of domesticity but also an appealing one. "That must be what it's all about," he sings. Maybe it is, maybe it isn't.

"Knockin' on Heaven's Door"

From: Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid (1973)

As "Knockin' on Heaven's Door" plays in the 1973 movie Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid – in which Dylan himself appears as the character "Alias" — Sheriff Colin Baker is dying from gunshot wounds. The song also stands out among the mostly instrumental country-folk tracks on the movie's soundtrack. There's a hymnal quality to it, with Dylan's voice supported by backing singers. And even though it was written specifically for the film, "Knockin' on Heaven's Door" has become more universal than Dylan intended. In 1973, as the Vietnam War continued, lines like "I can't shoot them anymore / That cold black cloud is comin' down" transcended the big screen. Drummer Jim Keltner was so moved in the studio that he "actually cried while we were recording it.”

"Big Yellow Taxi"

From: Dylan (1973)

Dylan's eponymous 1973 LP is sometimes referred to as Columbia's Revenge because it was released by the label without input or consent from Dylan. The album features a half-hour of previously recorded covers and traditional songs, including Dylan's version of Joni Mitchell's "Big Yellow Taxi" that was recorded just two months after the song's original release. Dylan swaps one lyric: Mitchell's "big yellow taxi" that takes away her "old man" becomes a "big yellow bulldozer" removing house and land. "We are like night and day, [Dylan] and I,” Mitchell said in 2010. Perhaps, but Dylan heard something in Mitchell's classic that made him want to give it a try.

"Forever Young"

From: Planet Waves (1974)

In the years he'd been off the road in the late '60s, Dylan had become a father and experienced something that resembled a normal family life. His feelings for his children came through in Planet Wave's "Forever Young," which was written for his small son. There's no hidden agenda in "Forever Young." Two versions of the song - one ballad style and one more up-tempo - were included on the album. "We only did one take of the slow version of 'Forever Young,'" producer Rob Fraboni said in Clinton Heylin's 2000 book Bob Dylan: Behind the Shades Revisited. "This take was so riveting, it was so powerful, so immediate, I couldn't get over it." A passing comment from someone else in the studio about Dylan turning "mushy" could have led to the slow version being removed from the album, but Fraboni convinced Dylan to leave it on.

"Simple Twist of Fate"

From: Blood on the Tracks (1975)

Selecting just one song from 1975's Blood on the Tracks is near impossible; the collection of songs as a piece gives the LP its tender, wounded quality. But "Simple Twist of Fate" is a breathtaking moment. Dylan shifts from a third-person perspective at the beginning of the song to first-person by the end. Like many of Dylan's best songs, including Tracks' "Tangled Up in Blue," "Simple Twist of Fate" has no chorus but instead returns to the title in the last line of each verse. On his 1978 live album Bob Dylan at Budokan, he introduced the song plainly: "Here's a simple love story. Happened to me."

"Tears of Rage"

From: The Basement Tapes (1975)

The Basement Tapes, Dylan's collaboration with the Band, was largely conceived within the walls of the group's Big Pink home near Woodstock, N.Y. With no plan, the musicians were free to explore whatever came up. "Tears of Rage" was cowritten with the Band's Richard Manuel. "[Dylan] came down to the basement with a piece of typewritten paper," Manuel recalled to the Woodstock Times in 1985. "And he just said, 'Have you got any music for this?' ... I had a couple of musical movements that fit ... so I just elaborated a bit because I wasn't sure what the lyrics meant. I couldn't run upstairs and say, 'What's this mean, Bob: 'Now the heart is filled with gold as if it was a purse'?'" The gospel-influenced song has been widely interpreted as "anti": anti-war, anti-materialism. But it's best summed up by the last line of the chorus: "Life is brief."

"Hurricane"

From: Desire (1976)

The opening line of "Hurricane" — "Pistol shots ring out in the barroom night" — immediately sets the scene for the story of Rubin Carter, a Black middleweight boxer who "coulda been the champion of the world" but was arrested for triple murder, tried and sentenced to life in prison by an all-white jury. Dylan took some liberties in his retelling of Carter's story, but there's no denying the speed and fervor with which "Hurricane" moves. It would be years before the falsely convicted Carter (and another man tried for the same crime) was free, but in 1976, Dylan knew he had a voice that the boxer did not. "Hurricane" was an opportunity to use it.

"Changing of the Guards"

From: Street-Legal (1978)

"Changing of the Guards" is rich with imagery, even if the imagery doesn't make much conventional sense. It chugs along at a rolling pace, peppered with words the backing singers throw in somewhat messily behind Dylan, who hasn't performed the song since 1978. "It means something different every time I sing it," he said in an interview that year. "'Changing of the Guards' is a thousand years old." It seems a warning, too, for whatever is next to come. "Eden is burning," he sings, "either getting ready for elimination or else your hearts must have the courage for the changing of the guards." In other words, the times are a-changin'��again.

"Slow Train"

From: Slow Train Coming (1979)

Dylan's transition into evangelical music has been one of the most widely discussed moves of his long career, but examining it too deeply is a futile exercise. What he faithfully believed in doesn't detract from the direction he took his sound, particularly with Dire Straits guitarist Mark Knopfler, whose dry, biting style gave the music new textures. Slow Train's title track is one of the LP's most secular, taking on pompous nationalist ideals and greed disguised under false notions of morality. "The enemy I see wears a cloak of decency," he sings. It's Dylan holding up a mirror just as he'd been doing since the beginning of the '60s.

"Pressing On"

From: Saved (1980)

"Pressing On" begins with an undemanding, gospel-infused piano intro, followed by Dylan offering one of his most captivating vocal performances of the decade. The sincerity in his voice lasts until the final note. If Dylan led a church sermon, this is what it would probably sound like.

"Every Grain of Sand"

From: Shot of Love (1981)

There are many clear biblical references throughout "Every Grain of Sand," but it's not the reference to Cain or wrestling with temptation that elevates the song from the rest of Shot of Love — it's Dylan's excruciating vulnerability, at once deeply personal and painfully universal: "I have gone from rags to riches in the sorrow of the night." He also pauses to consider that not even God can be there for him at every step of life's journey: "Sometimes I turn, there's someone there, at times it's only me."

"I and I"

From: Infidels (1983)

Infidels didn't drop the religious imagery altogether, but it did mark a return to the Dylan fans wanted to hear. But that's part of the problem. In the reggae-influenced "I and I," he appears to grapple with the gap between his public portrayal and his private life. "Someone else is speakin' with my mouth, but I'm listening only to my heart / I've made shoes for everyone, even you, while I still go barefoot." Dylan's band here is one of his best: Knopfler and Mick Taylor on guitar, Alan Clark on keyboards, Robbie Shakespeare on bass and Sly Dunbar on drums.

"When the Night Comes Falling From the Sky"

From: Empire Burlesque (1985)

An earlier take of "When the Night Comes Falling From the Sky" - which included two members of Bruce Springsteen's E Street band, pianist Roy Bittan and guitarist Steven Van Zandt - is more upbeat than the version that ended up on the album. But the Empire Burlesque take includes two of Tom Petty's Heartbreakers - guitarist Mike Campbell and bassist Howie Epstein - and is the LP's best song. The chord progression is somewhat familiar, like a revamped "All Along the Watchtower" with synthesizers. "When the Night Comes Falling From the Sky," like most of Empire Burlesque, is a fascinating product of its era and Dylan's time in it.

"Brownsville Girl"

From: Knocked Out Loaded (1986)

The crown jewel of Knocked Out Loaded, "Brownsville Girl," clocks in at a little more than 11 minutes. Cowritten by playwright Sam Shepard, the song's narrative can sometimes be difficult to follow — one moment the singer is speaking to an ex-lover, and the next he's trying to recount the details of a movie starring Gregory Peck. Maybe it's his way of distracting himself from his lost love, or maybe he sees something of himself in the drama: "Something about that movie though / Well I just can't get it out of my head / But I can't remember why I was in it / Or what part I was supposed to play."

"Silvio"

From: Down in the Groove (1988)

Dylan and the Dead — it's a better combination than you think. Take "Silvio," cowritten with Grateful Dead lyricist Robert Hunter and featuring backing vocals from Jerry Garcia, Bob Weir and Brent Mydland. It's the liveliest spot on Down in the Groove, rhythmic and bluegrassy. The Dead benefit from Dylan's cut-to-the-chase songwriting while Dylan reaps the benefits of the Dead's earthy, jovial playing. A symbiotic sound that stands out on the album.

"What Was It You Wanted"

From: Oh Mercy (1989)

"What Was It You Wanted" smolders like little else on Oh Mercy. For most of the '80s, Dylan was constantly asked "What happened?" He flipped those questions back here: "Is the scenery changing? / Am I getting it wrong?" he asks shrewdly. "Where were you when it started? / Do you want it for free? / What was it you wanted? / Are you talking to me?" Dylan closes the song with a cutting harmonica solo - a nod to the old Dylan in a new context.

"Unbelievable"

From: Under the Red Sky (1990)

A lot is happening on Under the Red Sky, with its many guest appearances and no real theme. Some songs are new, others were left over from the Oh Mercy sessions. But Al Kooper's organ and keyboard in "Unbelievable," combined with Waddy Wachtel's guitar, make for some energetic boogie rock.

"Tomorrow Night"

From: Good as I Been to You (1992)

Dylan's first album to not include any original songs since 1973's Dylan, Good as I Been to You was a pleasant surprise for many fans. "Tomorrow Night," a too-sweet love song performed by bluesman Lonnie Johnson in 1948 and Elvis Presley in 1954, among others, finds Dylan in a relaxed state. There's no straining here, only a man with his guitar and harmonica singing a song to the girl he loves.

"Broke Down Engine"

From: World Gone Wrong (1993)

Ten years before the release of World Gone Wrong, Dylan sang, "No one can sing the blues like Blind Wille McTell" in the Infidels outtake "Blind Willie McTell," which finally saw the light of day on 1991's The Bootleg Series Volumes 1–3. Dylan's take on McTell's "Broke Down Engine" ramps up the speed, pushing the limits of the song's original tempo. But like McTell, Dylan slaps the body of his guitar as he sings "Can't you hear me baby, rappin' on your door?"

"Not Dark Yet"

From: Time Out of Mind (1997)

The poignant centerpiece of Time Out of Mind, "Not Dark Yet" was kneaded through various versions before Dylan settled on this one. The song's existentialism is borderline suffocating at points, yet there's an unshakeable sense of resiliency as he sings, "I was born here and I'll die here against my will." The inevitably of death will eventually affect us all, but few have put the reality to words so candidly as Dylan does in "Not Dark Yet."

"Mississippi"

From: "Love and Theft" (2001)

When he was young, Dylan absorbed the rugged ramblings described in Woody Guthrie's music, from sea to shining sea and a whole lot of everything else in between. Now he was that comfortably weary traveler, having crisscrossed the planet more times than he likely ever imagined. "I been in trouble ever since I set my suitcase down." This is the essence of "Mississippi," culled from the Oh Mercy sessions from a decade earlier. "I’ve been criticized for not putting my best songs on certain albums," Dylan said at a 2001 press conference, "but it is because I consider that the song isn’t ready yet."

"Ain't Talkin'"

From: Modern Times (2006)

Dark, brooding, vengeful and apocalyptic, "Ain't Talkin'" does what all good album-closing songs should do: make you want to start the record again from the top. The bitter wanderer walks, "heart burnin', still yearnin,'" murder on his mind: "If I catch my opponents ever sleeping, I'll just slaughter 'em where they lie." A single major chord at the end of the song provides the only glimmer of hope.

"I Feel a Change Comin' On"

From: Together Through Life (2009)

Dylan never clarifies what exact change he feels coming on. It doesn't matter anyway: "Well now what's the use in dreaming? / You got better things to do." Mike Campbell plays two great guitar solos stacked nicely against Donnie Heron's accordion. Dylan also spares a line to address his legacy: "Some people, they tell me, I've got the blood of the land in my voice."

"Must Be Santa"

From: Christmas in the Heart (2009)

Faith didn't have anything to do with Dylan's decision to record an album of Christmas songs. "It's so worldwide and everybody can relate to it in their own way," he said of holiday music. If you have not seen Dylan's music video for "Must Be Santa," one of the LP's most amusing and downright silly songs, it's worth a view. Plus, it was all for a good cause: All of Dylan's royalties from the sale of Christmas in the Heart continue to be donated to various charitable programs in the U.S. and U.K.

"Pay in Blood"

From: Tempest (2012)

The slightly funky upbeat tempo of "Pay in Blood" juxtaposes its savage lyrics. Before he recorded the song, Dylan sang it for Elvis Costello in 2011. "Each time the chorus line came around," Costello recalled of the line "I pay in blood, but not my own," "it was delivered with a different flourish: a swashbuckler’s panache, a black comical riposte, held with a steady gaze, tossed away with a wicked laugh or a ghost of a smile."

"Why Try to Change Me Now"

From: Shadows in the Night (2015)

Dylan made one thing clear when it was announced that he was releasing an album of Frank Sinatra standards: "I don't see myself as covering these songs in any way," he said at the time. "They've been covered enough. Buried, as a matter a fact. What me and my band are basically doing is uncovering them. Lifting them out of the grave and bringing them into the light of day." The arrangements throughout Shadows in the Night drip with melancholy, but there's something particularly striking about "Why Try to Change Me Now"'s lyrics as crooned by Dylan: "Why can't I be more conventional?"

"Skylark"

From: Fallen Angels (2016)

"Skylark" is the only song on Fallen Angels not recorded by Sinatra. How purposeful Dylan's choice was to include it here is unknown, but his take on the standard is memorable for its looseness, Donnie Herron's viola and an exceptionally smooth vocal.

"I Could Have Told You"

From: Triplicate (2017)

There are several highlights to Triplicate, including "I Could Have Told You," which displays Dylan's voice aged like wine. Support by Tony Garnier's low bass-bowing, it's one of the trio of standard albums' finest moments.

"Goodbye Jimmy Reed"

From: Rough and Rowdy Ways (2020)

A few weeks into the COVID-19 pandemic, Dylan's 39th album, Rough and Rowdy Ways was announced. It was a return to original material after a trio of standards records and some of his best work of the 21st century. Prescient and historical, fresh and familiar, the LP contains multitudes. If you listened to nothing else on the album but "Goodbye Jimmy Reed," a foot-tapping tribute to the late blues guitarist, you'll come away with inevitable knowledge: Dylan, in his 80th decade of life and 60th of music-making, has still got it.

Bob Dylan Albums Ranked

Gallery Credit: Michael Gallucci

More From The Moose 94.7 FM